Maria Kaparaki

On September 2, 2021, the Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis passed away. He was born in 1925 in Chios, lived for almost a whole century, has produced an extremely rich artistic oeuvre and had an intense political and militant activity for the greatest part of his life.

He was involved with a very wide range of music genres. In addition to his enormous folk work, which launched his career and popularity, he wrote music for films and theatre performances, oratoria, chamber music, ballets and symphonies, leaving behind a gigantic discography of hundreds of works.

His universal recognition and reputation surpasses that of any other Greek artist. He has given concerts in many countries abroad; his compositions have been performed by world-famous artists.

For decades, Theodorakis never stopped creating; changing the landscape of Greek music to an extent that few composers have managed to do. The mark he left on folk music in particular cannot be easily captured. He managed in a unique way to combine contemporary popular music with Greek poets, and the European art nouveau element with the Greek folk element.

The political contribution of Mikis Theodorakis to the great struggles of the 20th century

At the same time, Theodorakis became known as a symbol of the Greek -and not only the Greek – peoples’ struggles, not only for his artistic work, but also for his rich political activity and involvement with all the great movements that shook Greece in the 20th century :the antifascist guerilla resistance during the second World War, the December 1944 battle for the control of Athens between the British troops and the Communist Party-led EAM (National Liberation Front), the ’46-‘49 Civil War between the Democratic Army and the US puppet government and the struggle against the military junta of ‘67-‘74.

At the age of 18, he joined EAM and shortly afterwards the Greek communist party (KKE). He took part in the National Resistance against the Nazi invasion and in December 1944 he fought in the Battle of Athens. After the December battle, he was persecuted by the police and went underground in Athens, until he was arrested in 1947 and sent into exile on the island of Ikaria. Following the general amnesty granted by the Sofoulis government in September 1947, Theodorakis went underground again until he is once more arrested and sent into exile in Ikaria, this time under “disciplined living conditions”. Shortly afterwards he was sent to Makronissos, where he was brutally tortured to the point of paralysis. After his dismissal from Makronissos in 1949, he left for Paris and returned to Athens in 1950. He left again with a scholarship for studies in Paris in 1954, and returned to Greece in 1960. In 1963 he was elected president of the newly founded mass left wing organization Lambrakis Youth, and in 1964 he was elected a member of parliament with the United Democratic Left (EDA) front.

Immediately after the coup on 21 April 1967, he went underground and a few days later he and others founded the first resistance organization against the dictatorship, the Panhellenic Anti-Dictatorial Front (PAM), to which he was elected president. The regime banned his music and Theodorakis was arrested in August of the same year. Following his arrest, he suffered imprisonment in the infamous “Bouboulinas” prison with torture, solitary confinement, etc. After a long hunger strike he was transferred to Averoff prison.

A storm of protests erupted at that time abroad by well-known personalities and played a major role in his release. He was then sentenced to home confinement with his family in the village Zatouna in Peloponnese, until he left again for Paris in April 1970 and returned to Greece after the fall of the dictatorship.

Theodorakis was a fighter, but had not adopted a firm political basis and approach, which resulted in him committing several political mistakes over the years. In ’74 he supported the right-winger Karamanlis, while in the ’90s he collaborated with Nea Dimokratia, the right-wing party, achieving the third place on the national ballot and becoming a minister “without portfolio”. This decision caused great disappointment to large sections of society, and so did his recent stand on the “national” issue concerning the name of the Republic of Macedonia and his participation at rallies together with the far-right and fascists.

These mistakes are not minor, nor can they be forgotten and erased, however much one admires his artistic work. On the contrary, those who appreciate his art and his great contribution to so many movements are the ones who become the harshest critics of his political inconsistency and his unacceptable -at times- positions. This criticism is not only legitimate, but also necessary, if we want our struggles to move forward, if we want society to change, if we want to see the collective vision that he so talentedly described in his songs put into practice.

At the same time, nothing prevents this criticism from coexisting with recognition and appreciation for his enormous contribution to popular struggles and culture. None of the above detracts from the importance of Theodorakis’ own political contribution in the past and the significance of his artistic, political and social work.

A pillar in the history of the Greek political song

Mikis Theodorakis’ work has been undoubtedly the backbone of Greek political music. His political songs have been inextricably linked to all the great struggles of the 20th century, to the struggle of the oppressed for freedom and justice, to the history of the country and of the Left. The sufferings, the exile, the sacrifices, the defeats, but also the courage, hope and visions of the Greek people were reflected in Theodorakis’ work and marked by it.

His albums Epitafios, Romiosyni, The Ballad of Mauthausen, Axion Esti, Canto General remain unmatched to this day, both conceptually and musically. At the same time, albums such as The Eighteen Small Songs of the Bitter Fatherland, Songs of Struggle, Songs of Andreas, Songs of Exile were also much loved and sung.

Speaking about the album Romiosyni, the composer has said in an interview:

“Romiosyni was brought to me at home by prisoners’ wives many years ago… But the manuscripts were put aside and covered by other ones. They were lost. They were forgotten. Until that very moment when some hand (without knowing how or why) retrieved them and laid them on the piano. This was preceded by clashes in Piraeus with the police, my savage beating and abuse, events that affected me deeply. So much that, as soon as I read the first verse, “These trees cannot settle with less sky…”, I sat down, as I was, covered in mud and blood, composed Romiosini all at once.”

And of course, as is always the case with great art, Theodorakis’ political songs influenced not only the generations that lived through all these historical events. The spirit of resistance, solidarity, hope, universality and collective memory that runs through his music has continued to fascinate subsequent generations and is still alive today.

Selected political songs

► Το σφαγείο (Το μεσημέρι)

► Διότι δε συνεμορφώθην

► Όταν σφίγγουν το χέρι

► Το Γελαστό Παιδί

► Μην ξεχνάς τον Ωρωπό

► Οι πρώτοι νεκροί (Πάλης ξεκίνημα)

► Θα σημάνουν οι καμπάνες

► Ένα το χελιδόνι

► Σωτήρης Πέτρουλας

Setting music to poetry

Theodorakis was the first Greek composer to set music to the work of great poets. Starting with the great “Epitaph” by G. Ritsos in 1960, he paved the way for other composers and other unsurpassed works. Ritsos, Livaditis, Anagnostakis, Gatsos, Varnalis, Seferis, Elytis, Karyotakis, Lorca, Neruda are some of the most famous poets whose work the composer dealt with.

The music he set to poems is considered one of the most important aspects of his work. It has been tremendously welcomed by the popular layers and succeeded in bringing the high art of poetry to the lips of the people en-masse. After all, only a major artist of this range would have been able to combine the sound of traditional bouzouki and the beautiful voices of folk singers with great poetry, achieving the composition of masterpieces that are still sung to this day.

Ritsos, referring to Theodorakis’ music for his poems, had said:

“It made a terrible impression on me, but is it possible for poetry to find a complete match with music? Until recently I was thinking that each art is self-sufficient and does not need any help from another. But when you created the music for the Epitaph, and later, of course, for Romiosyni, which was your great glory, I really said that here is a way for poetry to reach through music those people whom it would perhaps never reach.”

Selected poets set to music

► Την πόρτα ανοίγω το βράδυ

► Κράτησα τη ζωή μου

► Οι μοιραίοι

► Αυτά τα δέντρα

► America Insurrecta / Ξεσηκωμένη Αμερική

► Της αγάπης αίματα

Mikis’ folk songs

In addition to his great poetry and political songs, which he uniquely combined with the folk element, Mikis Theodorakis composed a series of folk songs that referred to the suffering, poverty, exile, love, pride and joys of the Greek people in a way that few artists have achieved.

Of course, all the great lyricists with whom he worked, played an important role in this direction. Some of them gave excellent examples of writing in Mikis’ popular songs. At the same time, the fact that great folk singers of the time sang them, such as Grigoris Bithikotsis, Mary Linda and Stelios Kazantzidis, largely contributed to Theodorakis’ songs being widely loved by the people.

Theodorakis himself, in a speech on the history of Greek folk song, had stated:

“…The years immediately after the German occupation were rich in creating folk melodies, which are now considered classical… The people look at their faces, as if in a mirror, and are frightened – they want to hear sounds that are loud, meaningful, sounds that in turn reflect all their anguish, their pain and their hopes.”

Selected folk songs

► Δραπετσώνα

► Βράχο-βράχο

► Απρίλη μου

► Βρέχει στη φτωχογειτονιά

► Σε πότισα ροδόσταμο

► Το παλληκάρι έχει καημό

► Της ξενιτιάς ( Φεγγάρι μάγια μου ‘κανες )

An artistic work that belongs to society and the people’s struggles

The death of Mikis Theodorakis reminded us how the system has very consciously insisted for decades on portraying him as an isolated, a national, de-politicised figure who always kept equal distance from political forces. It also reminds us how the ruling class struggles to silence the great political wealth of his work and, above all, to condemn to oblivion the movements that identified with it. But the world knows well that the political ancestors of those who now preach “national mourning” were the ones who hunted down, exiled, tortured and imprisoned not only the composer himself, but above all the thousands of militants whose voice he expressed.

The singer Pavlos Sidiropoulos had said

“… an artistic work, when it leaves the hands of its creator, acquires its own personality, its own identity, according to which its course is charted”.

This seems to apply to the case of Mikis Theodorakis perhaps more than to any other creator. A large part of his work has been appropriated by the society and its popular struggles to such an extent that it seems to have become detached from the composer and has charted its own independent path.

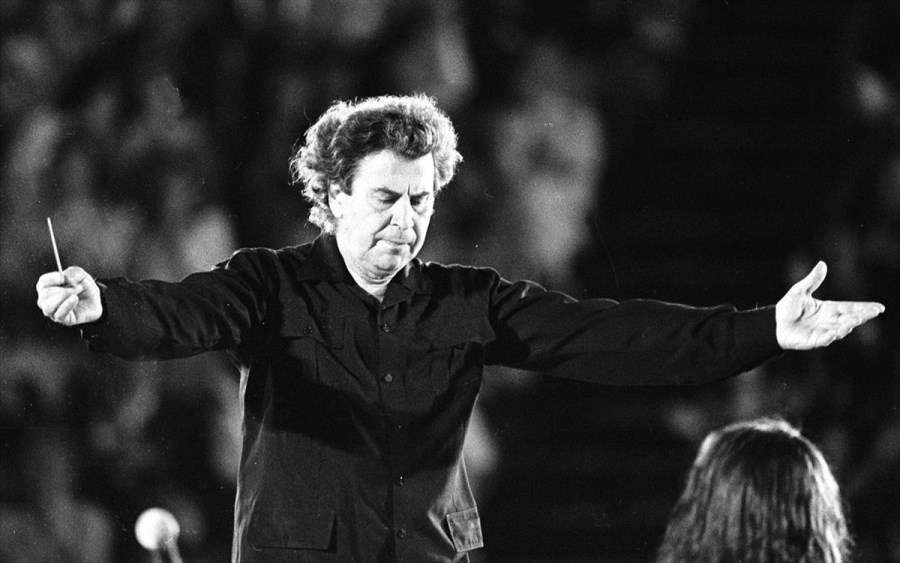

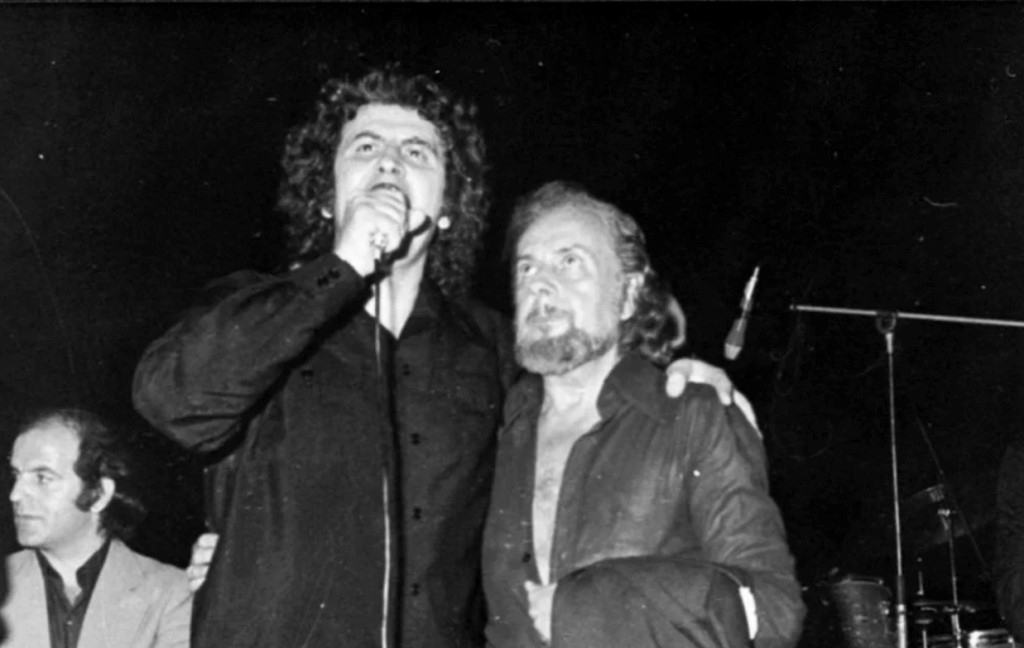

No matter how much they try to do otherwise, we know well that this part of his work will never be endorsed by the establishment. It will always belong to the people who clandestinely listened to Theodorakis’ songs during the Junta risking their own lives: to the mass of people in the streets of Athens celebrating the fall of the dictatorship, lifting in their arms the composer who had just returned from exile, to the thousands of people at his concert in the packed Karaiskakis stadium in 1974, chanting slogans like “People Remember November[1]”, “ESA[2] – SS, torturers” and “Give the Junta to the people”, to the political prisoners who sang his lyrics in prison and exile, to take courage, to the teenagers who still listen to his songs at the rallies commemorating the revolt of the Polytechnic school and are moved by them.

He will always belong to the movements and the popular strata that identified his music with their passion for freedom and justice, to those who – even in the cruelest and darkest times of history- stubbornly refused to “comply with the instructions” (as he sang in one of his most famous songs).