Nigel Smith

July 5th marks the 75th anniversary of the founding of the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom.This should be the signal for joy and celebration but it is instead an occasion of deep concern and sadness. The NHS is on its knees and is under attack as never before. The current Conservative government and the Labour opposition are intent on dismantling what was at one time an institution that was one of the most humane and civilizing in the history of the planet.

The ideas behind the NHS

The founding of the NHS and the ideas behind its foundation followed a long period of thought and consideration. Following the First World War and apparent throughout the War, it was clear that the health of the British people was poor. During the War the British generals had noted that Australian troops were bigger and fitter than British ones and therefore more able to succeed in the brutality of the bloodbath they were being thrown into. Dissatisfaction with the War and fear of revolution in Britain led to the British, Liberal prime minister, Lloyd George, cynically promising that the troops would return to a “land fit for heroes.” He appointed Lord Dawson, a London doctor, to oversee a commission on health that would look into improving health provision. Amongst other things, this commission looked at the new health system being introduced by the Bolsheviks in Russia, following the Russian Revolution and was impressed by its success and innovation. However, the Dawson plan, like so many other commissions and enquiries was shelved. The promise made by Lloyd George was a callous delaying tactic, waiting for the public mood to subside.

During the Second World War and following it, there was another drive to improve British healthcare. Between the Wars, the general health of the British people was poor and many were not covered by any kind of health insurance. In fact, if a worker wanted to call out a General Practitioner (GP), then it would prove to be expensive and ordinary workers were reluctant to have to seek help from a doctor because of the cost. In my own family a story is told of my mother lying ill in bed and her parents delaying sending for medical assistance because of concerns over the cost. Eventually a doctor was called. She was diagnosed with diphtheria, a common, potentially fatal childhood illness, which was by that time treatable with an antitoxin. She recovered, but her cousin who she caught it from, tragically died because his parents failed to get help in time. These grizzly calculations were ended with the introduction of the NHS.

WWII

During the Second World War a realisation was growing amongst the British people that things shouldn’t return to the conditions that existed before the War. Prior to the War the rail network had been starved of resources, along with other public utilities. Hospitals were in insufficient numbers to meet the needs of the sick and working-class areas were poorly served. During the War itself public health improved as did the general health of the British people. This was attributed, ironically, to food rationing and advances in the health services. Food rationing meant that the poor, for the first time since the beginning of the industrial revolution, were provided with sufficient food to meet their dietary needs. The creation of the Emergency Medical Service meant that the numbers of hospital beds was increased and hospital staff could be flexibly deployed towards poorer areas, where the need was greatest. Local blood transfusion and public health laboratories were created and the ambulance service was radically improved.

The feeling of discontent at inter-war conditions continued to grow. People began to see that even during a war, things could be made better. The government felt compelled to launch the Beveridge Report on social welfare. The progressive findings of the report were read widely by the population and the people were enthusiastic about those findings. This report could not be ‘kicked into the long grass’, as the Dawson report had been. The capitalist class was also lacking confidence and was aware that rebuilding the British infrastructure following the war was not a project they wanted to engage in. There was little or no profit to be made from mass healthcare, railways and other obsolete and decrepit layers of infrastructure.

The creation of the NHS

The Labour Party won the 1945 general election with a programme that included the creation of the National Health Service as well as the nationalisation of the major public utilities. Aneurin Bevan became Minister of Health. Bevan made the nationalisation of the mostly dilapidated hospitals a priority. The NHS was introduced in 1948, but Bevan compromised with GPs and allowed them to stay self-employed, but paid by the NHS. He also failed to nationalise the profitable pharmaceutical companies. This was a significant concession to the capitalists, where the state bailed out the loss-making elements of the economy whilst allowing the profitable ones to remain in private hands and for profit. This pattern of state support for inefficient capitalists has been repeated ever since, with the British rail network a prime example.

However, the capitalist class would not allow these experiments with socialist policies to remain forever. They pushed back against the NHS. As early as 1951, Bevan resigned from the Labour government because it succumbed to pressure from the capitalist class and introduced charges for dentures and spectacles. In 1952 the new Tory government brought in prescription charges, which were removed by Labour in 1965, only to be reintroduced in 1968.

Privatisation and corporatisation

Both Tory and Labour knew that the NHS was incredibly popular and were reluctant to meddle with its underlying principle. They sought instead to chip away at the institution incrementally instead. When Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister, she secretly looked at major structural adjustments to the NHS, but was persuaded that these would lead to a back-lash from the British people. Instead, she tried to persuade the population that the private sector could be more efficient in running facilities services – cleaning, cooking, grounds maintenance etc. The privatisation of cleaning services led to significant increases in hospital infections and many of the cleaning contracts were taken back in house. Thatcher spouted the mantra often repeated by Tories, that the “health service is safe with us”.

In 1991, the NHS and Community Care Act was enacted by John Major’s Tory government. This introduced corporate management structures into the NHS. The NHS had never been run by its workers, but doctors and, to a lesser extent, nurses were given a lot of autonomy within hospitals. The corporate approach meant that medically unqualified business people began the process of transforming the NHS, along business lines. Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs) were also introduced. PFIs have proved to be a major block to long-term improvement of the NHS. They offered private capital for infrastructure projects, but the contracts themselves tied hospital trusts into contracts that would prove to be financially crippling in the long term.

Tony Blair’s New Labour government embraced the corporatisation of the NHS and the use of PFIs increased massively. Blair’s interest was to feed the capitalists with government money for short-term gain and forget about the long-term needs of the NHS. New Labour accelerated privatisations within the NHS, contracting out increasing numbers of services and signing a ‘Concordat’ with private companies in 2000. In 2003 Foundation Trusts were created. These accelerated the privatisation process still further.

In 2012 the Tory – Liberal Democrat coalition government introduced the Health and Social Care Act. This act reflected New Labour thinking around marketisation in the NHS and increased once more the speed of the process. Trusts were regulated by Monitor, an organisation made up of almost exclusively none medically trained business “experts”. Management consultancy firms such as McKinsey were brought in to focus hospitals more and more on cost-cutting rather than patient care.

NHS in crisis

Today, the Health and Care Act of 2021 has created forty-two Integrated Care Boards (ICBs). These are huge US style corporate bodies controlling the entire NHS system. Prescription management has been delegated to private companies and the NHS has lost control of its ability to manage effectively the cost of drugs. The inefficiency of the private sector is hidden behind the mask of secrecy. Questions are asked by patients and activists but the response is all too often that the issue is commercially sensitive, therefore the Trust doesn’t have to give an answer. Trusts are also blocking scrutiny by the public, which was never effective but at least ordinary allowed people to gain some insight into the machinations of the system.

All of these attacks and many others, too numerous to mention in this short report mean that the NHS today is in crisis. Nurses, doctors and other staff have seen their pay eroded by huge percentages since 2008. Junior doctors pay for example has reduced by 26% in real terms. Working conditions and the ability for staff to do a decent job have also been a major problem. In a recent report, The King’s Fund found that the NHS was being squeezed to death by the Tories. It found that standards of care, across the board were declining and the NHS was beginning to compare unfavourably with health services in similar countries in terms of health outcomes, pay and conditions of work. It also found that in the UK life expectancy was falling, ill-health was increasing and people’s lives were being unnecessarily lost. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine reported that in 2022 there were 23,000 excess deaths relating to an increase in waiting times in A&E (Accident and Emergency departments).

The Labour Party however is now showing its open hostility to the founding concept of the NHS. It talks about using the private sector more, to reduce waiting times. The private sector is given the straightforward and lucrative procedures such at knee and hip replacements and cataracts. Wes Streeting, the Labour shadow health secretary complained that the recent, Tory NHS Workforce Plan was “nicking” their ideas. This implies that the attack on pay and conditions that this plan advocates would coincide with Labours thinking. The plan itself is inadequate and will not successfully address the acute shortage of staff withing the NHS. Latest figures suggest that the NHS is short of 110,000 staff. Low pay and poor conditions of work mean that many staff who are recruited leave shortly after qualifying or during training. The NHS is simply unable to retain its staff. Doctors and nurses go abroad or to work in the private sector. Many able graduates are forced to train abroad in countries such as Bulgaria, because there are too few training places in the UK and because student fees are significantly lower abroad. They then often to go to work in Canada or Australia, rather than return to the UK once they qualify.

Fightback

Nurses, doctors and other NHS workers are fighting back for better pay. But another aspect of this fight is a genuine concern that they can no longer do their jobs properly because of underfunding and other structural issues. They are also more aware than anyone that patients are dying unnecessarily and that standards are falling.

The NHS remains popular with the British people, in spite of all the above. The attacks made against it are however clouded in complexity and secrecy and so most people don’t realise how critical things are for the service. The Covid Pandemic, did offer a brief window into the power of the NHS to succeed, but also the power of the state to fail dramatically and of the private sector to show its incompetence and inefficiency.

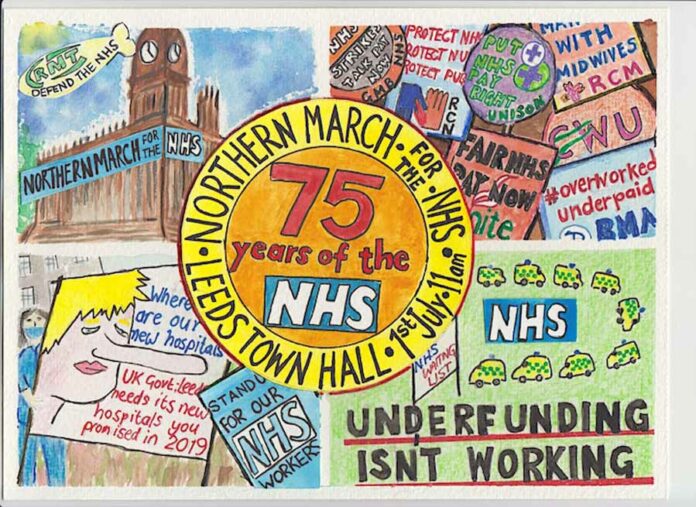

A recent rally and march in Leeds is just one example of the public getting behind the NHS. The march attracted several hundred NHS workers and activists and was warmly applauded by the public, but was much smaller than previous events. This is a trend that has been apparent since the pandemic, but could also be a sign of protest fatigue. There is a sense that we have marched before and protested before but nothing changes. People are also let down by the Labour Party, who they see as no better than the Tories.

New working class organ needed

What we need is a new political organ of the working class. The Labour Party no longer plays that role, but the formation of a new worker’s party seems a long way off. Labour is summarily expelling its best socialists with an email telling them that their membership has been terminated. The Labour lefts hang onto the coat-tails of the Party in a vain hope that they can win it back, when Sir Keir Starmer has made it clear that Labour in more for big business than it is for workers. Groups such as Enough is Enough (EiE) are set up, but can mutate into a means of activists letting off steam and offering no alternative to Labour. The EiE groups in Yorkshire, where I live, operate as independent bodies and get little or no support from any central organisation. They do important work, but there is little sense that the organisation is building nationally or is interested in building. The usual left Labour apologists are wheeled out to speak at rallies and nothing changes.

What is required is united action across the unions. Unions should be striking together and the Trades Union Council ought to be playing a prominent role in coordinating the strikes. The unions should also be looking, as the Rail, Maritime and Transport (RMT) union did when it helped set up the Trades Union and Socialist Coalition (TUSC), at coming together to build a worker’s party. Workers need to be showing their support on picket lines but also donating to and setting up strike funds that can help strikes be sustained over longer periods. The tactic of short-term strikes suits the tops of the unions but is not proving effective enough. Historically strikes in the UK used to be of longer duration and more successful. The call for a new worker’s party can also raise the political questions that are hidden from the people by the capitalist media and the elite. The real nature of the NHS – under worker’s control for example. The ideas of the benefits of properly funding healthcare and the widespread nationalisation of industries, including big pharma, under worker’s control could also be raised. Importantly, a new worker’s party could bring together all the disparate groups and activists under one umbrella and give them the means to spread the ideas of the nation being run for the benefit of all its people and not the rich. The awareness that the rich are exploiting the rest of us, is now well understood. What is lacking is a clear means towards an alternative. Workers and activists need to come together, refine their ideas and spread those far and wide – cut across the popular media and create their own dialogue: on the streets, in workplaces, cafes, schools and pubs.