Giorgos Kasampalakos

For the United States, the 1870s was a turbulent decade: it began at the height of economic growth and the opening of new trade routes. Rail networks were expanding at a frantic pace, both in the Southwest and the Northwest. The civil war was over and capitalist growth was sweeping the country. As historian Allan Nevins notes in his book Emergence Of Modern America:

“More cotton spindles began to spin, more iron furnaces were fired up, more steel was made, more coal and copper mined, more lumber chopped and sawed, more houses and stores built, and more factories of every kind established in those years, than in any other period of our earlier history.”

The Long Depression of 1873-1879 and the opulence of the magnates

The booming economy up to 1873 was followed by a terrible depression of six years, until 1879. The US looked like a bombed-out landscape during those 6 years. The textile mills were left empty of people and cloth, the mines remained empty holes, the ploughs and reapers rusted in the fields.

Two-fifths of the workers worked no more than 6-7 months a year, at a time when unemployment had reached 3 million. Wages had been reduced by more than 45% and they were no more than $1 in the majority of cases. People were wandering aimlessly on the streets, sitting bored in bars drinking beer bought on credit, wondering what had gone wrong and their lives were being ruined.

The situation was not the same for everyone, of course. Tom Scott, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, John Rockefeller (founder of the bank with the same name) and Andrew Carnegie, aka the steel emperor, personified the “successful entrepreneurs” who became leaders in their field during the Long Depression. The opulence and luxury enjoyed by this small, tiny group of tycoons appalled working class people. According to a newspaper:

“They fed their horses flowers and champagne (…) a lavish meal was given in honour of a little black dog wearing a diamond collar worth $15,000 (…) at a reception cigarettes were wrapped in $100 bills”.

Parsons-Spies and the demand for the 8-hour day

Continuous industrialisation was pushing up the number of industrial workers in a geometric progression. Thus, the Knights of Labor, then the main organised labour force, exploded from 28,000 members in 1880 to 700,000 in 1886. But by 1886, the American Federation of Labor, AFL, was formed.

Albert Parsons, son of the Reverend Jonathan Parsons and Elizabeth Tompkins, grew up with Aunt Hester, a black slave who looked after him when his parents died. He married a Mexican Indian, Lucy Eldine Gonzalez, moving to Chicago at the same time, just before the Long Depression of 1873.

In Chicago they witnessed first-hand the poverty, hunger, evictions and mile-long lines for bread that the economic crisis brought. During the harsh winter, the Parsons formed their political beliefs by watching the icy wind from Lake Michigan blow through the thousands of homeless people. The police’s violent crackdown on protesters was forever etched in Parsons’ memory; he joined the Social-Democratic Party, which was promoting the ideas of socialism and revolution, and the Knights of Labor in 1876.

August Spies, an immigrant of German origin, arrived in the United States in 1872. He began working in Chicago as an upholsterer, and in 1877 joined the Socialist Labour Party. In 1880, he began working as editor-in-chief of the anarchist journal Arbeiter Zeitung (Workers’ Newspaper).

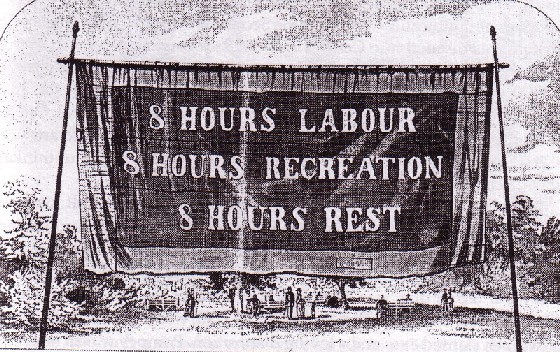

At the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (the AFL forerunner) convention in 1884, a resolution was unanimously adopted proposing that a nationwide rally of the entire working class be held on May 1 in Chicago to fight for the 8-hour day.

Warlike atmosphere

The country’s major newspapers launched a furious attack on the workers and the “anti-national” demand for the 8-hour day.

Melville E. Stone, founder of the Chicago Daily News wrote that

“a repetition of the Paris Commune riots can be easily foreseen.”

while the Chicago Tribune noted

“Every lamp-post in Chicago will be decorated with a communistic carcass if necessary to prevent wholesale incendiarism or prevent any attempt at it.”

The Daily Mail had already targeted those “responsible” in its editorial:

“There are two dangerous thugs in our city, one named Parsons and the other named Spies… Remember their names today. Watch them. Hold them personally responsible for any trouble created. Punish them personally if there is a riot!”

Parsons, Spies and other union leaders were feverishly preparing for the big day, May 1, 1886. They spoke at meetings, toured big factories, trying to rally as many as they could behind the 8-hour day strike.

A month before May 1, decisions to support the strike and the rallies had been taken by the unions of cabinetmakers, machinists, brickmakers, plasterers, butchers, shoemakers and many other trades.

It was estimated that 62,000 Chicago workers would go on strike, another 25,000 were demanding the 8-hour day but without a strike and 20,000 had already won a reduction in working hours.

May 1st- a peaceful demonstration

May 1st 1886 was a sunny day, despite the bitter morning cold. Despite the tension of the past few days, calmness prevailed in the city. The strike was a huge success. According to the Chicago Mail

“some 340,000 workers were on picket lines across the country, with 80,000 striking in Chicago.”

There was a festive atmosphere in the streets, the workers were dressed up and accompanied by their families, and they marched en-masse to the area where the speeches of the strike leaders were to take place.

The demonstration began and people headed towards the lake where speeches were made in English, Czech, German and Polish.

The demo consisted of all walks of the movement: the Knights of Labor, the American Federation of Labor, the blacks, the Irish, the Italians, the Bohemians, the Russians, the Germans, the Jews and ordinary people demanding the immediate implementation of the 8-hour day.

In the evening the crowd began to gradually disperse. The Kassandras of bloodshed were refuted. The newspapers that had predicted carnage now took back their supposedly accurate information and predictions. But the conflict was approaching…

The events at the McCormick factory

The next act of the 8-hour struggle was to be played out at the McCormick mower factory, which was also closed due to the strikes.

The police, on the orders of McCormick himself, had arranged to allow 300 scabs to break the strike, hoping to bring down the morale of strikers across the city. The workers waited for the scabs as the factory was closing. As soon as the strikers came out, before they could do anything, the guns of the police men turned on them and started firing at them. Two workers were shot dead, even though some newspapers talked of six fatalities.

Spies himself happened to be close to the massacre, and he reported the incident to his comrades, and a protest meeting was immediately arranged for the following evening, May 4, in Haymarket Square.

The events at Haymarket Square

When Parsons and Spies arrived at the square, they saw a large crowd, brimming with indignation and anger at the unjust loss of their comrades. Spies spoke to the crowd from a wagon that had been dragged to the corner of a cobbled street.

Behind the alleyway was the Des Plaines Street police station, headed by John Bonfield, aka “Black Jack” because of his brutal methods… Inside the police station there were 180 police officers, something Spies, Parsons and the other organisers of the rally did not know.

Parsons went up to the wagon to address the crowd, saying,

“I’m not here to stir anyone up, but to call a spade a spade.”

His speech ended at around 10 o’clock. Freezing raindrops coming from the side of the lake foreshadowed the storm that was coming. Sam Fielden took the floor. Suddenly there were shouts “Attention! The police!” The 180 police officers in the Des Plaines Street station appeared at the end of the street with batons in hand.

The momentary silence was cut in two by a red flash and a huge explosion that followed. Someone had thrown a bomb in the direction of the policemen. Panic ensued. The police were now shooting in all directions, the crowd running for their lives while dozens of fallen people were trampled. Furious police officers kicked, punched and killed. The official final death toll given by the authorities was 8 policemen and 4 protesters dead, but the actual number of dead workers, if you include the seriously injured who ended up dead in the following days, was more than 30. The Chicago Herald estimated at least fifty dead or wounded civilians laid in the streets that day.

Thirst for blood

In the headlines of the next day’s newspapers one can guess what was to follow. It was the beginning of the first “Red scare” campaign in the US.

The Chicago Tribune asked for the hanging of the strike leaders in public view.

Many suspected that the bomb was the work of provocateurs but up to this date there are no definite evidence to support or deny that claim.

In the days following the tragic events in Haymarket Square, almost all the union leaders of Chicago were arrested, Spies, Fielden and Schwab being the first ones. A few hours later George Engel, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg and Oscar Neebe, all Knights of Labor members, were also arrested.

Parsons, who immediately sensed the danger, managed to escape in the confusion. A few days later, hiding on a hill in Wisconsin, he learned that he too was one of the accused. Although he and his family had securely fled, he could not bear the thought that his friends and comrades were in danger. So, although he knew that to return would be tantamount to suicide, he decided to go back and surrender.

Statements of the accused

The defendants’ apologies took up whole pages in the press. Even the most avowed enemies of the workers’ movement admitted that the defendants held their heads high and did not sell out their ideas. Neebe, said among other things:

“I saw that the bakers in this city were treated like dogs. The baker bosses treated their dogs better than they treated their men. I said to myself: ‘These men have to be organized, in organization there is strength’; and I helped to organize them. That is a great crime. The men are now working, instead of fourteen and sixteen hours, ten hours a day, and instead of being compelled to eat slops like dogs and sleep on the stairways or in the barn, they can sleep and work whenever they please. I have helped to establish that, your honor. That is another crime. And I committed a greater crime than that. I went to work further, because I saw in the morning when I drove away with my team that the beer brewers of the city of Chicago went to work at 4 o’clock in the morning. They came home at 7 and 8 o’clock at night. They never saw their families, they never saw their children by daylight. I said to myself: ‘If you organize these men they can live like men. You can help to make good citizens out of them’.”

Parsons began his apology by recounting all the unjust persecution, even murders, that the militant workers had suffered at the hands of the army, the police and of course members of the vigilance groups, actions that were never investigated. He claimed that the bombing was an act of provocation by the private security Pinkerton company,

“The charge made by the labor papers that the monopolists were at the bottom of the Haymarket tragedy, and that the Pinkertons were employed to carry it out, supplies the key to the solution of the mystery as to who did throw that bomb”

Spies’ apology sharply raised the tone when, addressing the Judge Gary and the jury with a proud tone, he said:

“But, if you think that by hanging us, you can stamp out the labor movement – the movement from which the downtrodden millions, the millions who toil and live in want and misery – the wage slaves – expect salvation – if this is your opinion, then hang us! Here you will tread upon a spark, but there, and there, and behind you and in front of you, and everywhere, flames will blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out. The ground is on fire upon which you stand. You can’t understand it.”

The execution

On October 9, 1886, the verdict came out. As expected, all were found guilty. Seven got a death sentence, while Neebe got a 15-year imprisonment sentence.

Lucy Parsons went around the country, determined to save the lives of the seven men. To no avail, well known figures such as Bernard Shaw and William Morris sent letters of support and protest at the impending executions.

In a letter from his cell, waiting to be hanged, Parsons wrote

“And now to all I say: Falter not. Lay bare the inequities of capitalism; expose the slavery of law; proclaim the tyranny of government; denounce the greed, cruelty, abominations of the privileged class who riot and revel on the labor of their wage-slaves. Farewell”

Of the 7 men on death row, only 4 were eventually hanged. The day before the execution, Governor Oglesby turned the death sentences of Fielden and Schwab to life imprisonment, while that same night Lingg committed suicide (or was murdered in his cell).

On the morning of November 11, 1889, Spies, Fischer, Engel and Parsons were taken to the gallows. When the noose was wrapped around Spies’ neck, he said

“The day will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you are throttling today”…