Nikos Anastasiadis

This is the first part of our series of articles on the crisis of the 30’s

“This is an unprecedented situation, this is worse than 2008, this is worse than 1987, this is the worst crisis to hit financial markets since the Great Depression”

That’s according to Stephen Isaacs of Alvine Capital investment consulting company. The comparisons of the current crisis that began with the Covid-19 pandemic to the Crash of ’29 in the United States and the crisis that followed are becoming more and more frequent. Let’s see then what happened at that time, and what the differences and similarities with the current situation may be.

From prosperity…

After World War I and throughout the ‘20s in the US there was a prevailing climate of optimism, based on the role the country played in the war and its overall enhanced global position, as well as the rapid development of its industrial base. The “roaring ’20s” as they are widely known, with the massive expansion of construction, the car industry, the electricity power plants, etc, were the basis on which the “American Dream” was being built.

Indicatively, John J. Raskob, the businessman behind the Empire State Building and chairman of the Central Committee of the Democratic Party, two months before the ‘29 crash, said:

“everybody ought to be rich”

and went on describing that if someone invests a weekly income in the stock market, they will be able to get rich within a few years.

Respectively, US President Hoover stated in ’28:

“Given the chance to go forward with the policies of the last eight years, we shall soon with the help of God, be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation”

However, this optimism was based on shaky foundations, as it became evident a few months later.

… to the crisis…

As Marx predicted in Capital:

“It appears then, that capitalist production comprises conditions independent of good or bad will, conditions which permit the working-class to enjoy that relative prosperity only momentarily, and at that always only as the harbinger of a coming crisis”

Thus, the rise of the stock market could only cover for a while, but eventually not eliminate, the structural contradictions of the system. That is, the main contradiction between the social character of production (the fact that in order to produce products and services that society needs, there is a process where collectively people offer their physical and spiritual workforce) and the individual character of the appropriation of profits. Simply put, we are all working in order for a few to gain, and therefore poverty on the one hand and the over-accumulation of wealth on the other are inevitable, and eventually lead to crises.

At times, in order to avoid collapse, capitalism promotes lending- and actually any “casino” logic. It is no coincidence that the Ponzi scams began in the US in the 1920s. The biggest gamble of the time, however, took place in the stock markets.

… to the collapse…

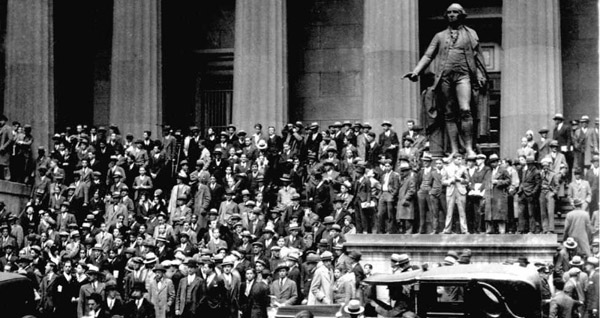

October 29, 1929 became known as the “Black Tuesday”. 16 million shares changed hands that day at the New York Stock Exchange. Billions of dollars were lost from the hands of investors. The stock market crash marked the beginning of a decade that was referred to as the “Great Depression”, the largest depression experienced in the industrial world to that date.

As one commentator of the time wrote, Wall Street (the stock market of New York) “lit up like a Christmas tree”. There was panic that day. When the bell that signaled the end of the day’s workings rang, the cleaners while collecting paper, tickertape, and sales slips (at the time all transactions were made with paper and with the physical presence of the brokers) found “torn suit coats, crumpled eyeglasses, and one broker’s artificial leg”!

… and misery

The crisis of ’29 meant that millions of people lost their savings. By ’33, almost half of the American banks had gone bankrupt. Unemployment rose from 3% in ’29, to 25% (officially) in ’33. The country’s GDP fell by 26% over the next five years.

But it wasn’t just in the US. The global GDP fell by 15% within 4 years, while world trade fell by 50%.

The crisis, along with the drought and dust storms that had hit the region around Oklahoma (named “the dust bowl”) led to more than a million poor villagers and land workers to the road to internal migration to the more fertile areas of California. This huge movement of impoverished people inspired John Steinbeck to write his earthshaking book, “The Grapes of Wrath”, and Woody Guthrie to create the “Dust Bowl Ballads”. Between 1930 and 1935, about 750,000 small family farms were confiscated by banks due to bankruptcies.

Workers’ wages plummeted. Even Henry Ford, an advocate of the “minimum wage” logic, who introduced the $5 wage in 1914, cut his workers’ wages by half. In the cotton plantations of the South, the workers were paid so little, that even the toughest ones, with the greatest output, made a maximum of 60 cents in a 14-hour workday!

The birth and marriage rates plummeted over the next decade, and “naturally” the crisis hit African Americans and minorities far more, with their unemployment rate being twice as high as that of the general population.

One can get a brilliant description of the situation from the lyrics of the song “Brother, can you spare a dime?”

They used to tell me I was building a dream

And so I followed the mob

When there was earth to plow or guns to bear

I was always there right on the job

They used to tell me I was building a dream

With peace and glory ahead

Why should I be standing in line

Just waiting for bread?

Once I built a railroad, I made it run

Made it race against time

Once I built a railroad, now it’s done

Brother, can you spare a dime?

Once I built a tower up to the sun

Brick and rivet and lime

Once I built a tower, now it’s done

Brother, can you spare a dime? […]

Struggle and solidarity

In every crisis obviously, phenomena of desperation develop but so do wonderful examples of class solidarity. In the United States of the 1920s, there was no “safety net” for the poor and the unemployed. The various charity organizations were completely disproportionate to the situation. In the face of the state’s refusal to provide assistance, people were trying to help each other. A great example of this are the teachers of New York and Chicago, who collected money from their salaries to help poor students, although many times they themselves would get the salaries with great delay.

Of course, the most important battles were fought in the workplaces. One of the most dynamic sectors was that of the car industry. Workers there faced massive layoffs and cuts (only in Ford 2/3 of workers were laid off). This led to the first mobilizations.

In March ’32 in Detroit, those who were still employed, those who were fired, and the unemployed, organized a march to the Ford factory, which was located at the outskirts of the city; the march was called the “Ford Hunger March”. Their demands included: rehiring the unemployed, providing funds for health care, ending racial discrimination in hiring, abolishing the use of company spies and private police against workers, and giving workers the right to organize unions. Workers’ placards read “We want bread, not crumbs”. The march was stormed by the police, as well as by Fords’ thugs, who used tear gas, truncheons and live bullets. Four workers were killed and one more succumbed a few months later.

In spite of that heroic struggle, a generalized reaction from the workers’ side took some years to unfold. As Trotsky explained, often the first reaction to the shock of the crisis is a “stunning effect” on the part of the working class. In an insightful text in’32 he writes:

“In the United States, the most powerful capitalist country, the present crisis has exposed terrible social contradictions. After a period of unprecedented prosperity, which astonished the whole world, a sort of fireworks of millions and billions, the United States suddenly passed to unemployment of millions of men, to a period of frightful poverty, of biological misery for the workers. A social upheaval of such formidable extent cannot but leave traces in the political development of the country. It is still difficult to determine just now –at least from a distance– what can be the radicalization of the American working masses. We can suppose that the masses themselves have been so taken unawares by the catastrophic crisis, of the general economy, have been so stricken and stunned by the unemployment or fear of unemployment, that they have not yet had time to draw the most elementary conclusions on the calamity which has befallen them. It takes time. But the conclusions will come. The vast economic crisis, which has taken on a social character, will be inevitably transformed into a crisis of political consciousness of the American working class. It is very possible that the revolutionary radicalization of large sections of the working class will take place not in the period of lowest economic conjuncture, but on the contrary, when there is a return to new activity, to a new upgrade”.

And indeed, the most dynamic struggles began to develop after the first 5 years of the recession, when the economy was back on the track of growth.

1934 – the class struggle returns

In the spring and summer of 1934 we had 3 very important strikes:

The strike of workers at the Autolite electrical goods company in Toledo. The strike lasted 5 days with daily battles between the 10,000 strikers and 1,300 men of the National Guard, leaving 2 strikers dead and 200 wounded.

The strike of drivers and transport workers in Minneapolis, from May to August. Workers blocked all trucks carrying goods in order to gain the right to form a trade union. Clashes with police were constant, culminating in the “Bloody Friday” of July 20th, during which two workers were killed by National Guard bullets and 67 were injured. The strike was organized very methodically by the Trotskyist forces of the region. The strike ended with victory for the workers.

The strike of the dock workers of the West Coast, which was centered around San Francisco, from May to July. In its attempts to end the strike, the police killed two strikers. The repression led to a general strike in San Francisco involving 150,000 workers which lasted four days, halting all activity in the area. Police and employers used the “communist conspiracy” scarecrow to curb the appeal of the strike.

All these developments had affected and shaped the overall situation in the labor movement. Thus, the most conservative American Federation of Labor (AFL) split and the most combative Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was formed, which in a short period of time was successful in organizing 5 million workers.

The workers struggle carried on in the following years with important moments such as: The occupation of the General Motors factories that began in late 1936 in Flint for 44 days by 2,000 strikers, who set up their own system of self-organization while repelling an armed attack by the army; and the fierce strike of the miners in companies that had refused to sign a collective agreement with their union in 19’37, with 67,000 strikers, thousands arrested, 18 dead and hundreds injured. The strike lasted five months but was eventually defeated.

Finally, there is the interesting story of the Farmers’ Holiday Association (FHA), which organized a mass refusal to sell their products under the slogan:

“Lets call a Farmer’s Holiday, a Holiday let’s hold. We’ll eat our wheat and ham and eggs, and let them eat their gold”

They demanded better prices for their products. They also set up roadblocks to stop the transport of agricultural products, as well as actions to stop the seizure of their farms. These were called “penny auctions”. When a bank put up for auction the farm of a poor indebted farmer, a large group gathered to “offer” a few pennies for it, while threatening and forcing out anyone who wanted to take advantage of the situation to buy their property cheaply. Thus, the auction would end with the bank being forced to accept a minimum price and the farm being returned to its owner.

Political repercussions

Obviously, a crisis of this magnitude cannot but produce political results.

Initially, the American establishment confronted it with the logic of business as usual. The “invisible hand of the market” would intervene after this “necessary correction” of the economy and would put it back on a trajectory of growth. Of course, they were not very much interested in the fact that millions of working class households would be destroyed through this “correction”.

Thus, President Hoover initially did not take any special measures, expecting the private sector to bring balance to the economy again. But as the years passed and the situation progressively deteriored, Hoover became one of the most hated presidents in the history of the United States, and led him to lose the 1932 presidential elections. The slums with the unemployed were called “hoovervilles” in his “honor”; the newspapers were called “Hoover blankets” (because the homeless used them to cover themselves) and the empty pockets hanging outside trousers were called the “Hoover flags”. Before the election, there were reports that some hitchhikers were holding signs that read: “If you don’t give me a ride, I’ll vote for Hoover.”

It was in this political atmosphere that Franklin Roosevelt, the Democratic candidate, won the election. His campaign program promised a policy of government intervention and spending to tackle the Great Depression. A phrase in one of his speeches about the need for a “New Deal” would go down in history and mark the next decade after his election.