The Portuguese legislative elections of January 30, 2022, gave a clear victory to the outgoing Prime Minister Antonio Costa and the Socialist Party. The two parties of the Left, the Communist Party and the Left Bloc, suffered huge losses. On the other hand, the far-right party Chega (which means “enough!”), also scored a significant rise and found itself in third place.

The Socialist Party (equivalent of the European social democratic parties) got 2.2 million votes and 41.7%, electing 117 out of 230 members in the parliament, securing an absolute majority. The Social Democratic Party (a conservative right-wing party), was expected to fight a close battle with the Socialist Party, but ended up with 27.8%, managing to maintain its forces. A smaller right-wing party, the Liberal Initiative, got 5% and 8 MPs, achieving fourth place in the Portuguese parliament.

Left: the big loser

There is no doubt that the Left is the big loser in the Portuguese elections. The fall of the Left, combined with a significant rise of the far-right, is a setback for the movement, which will now need to fight its battles from a worse position.

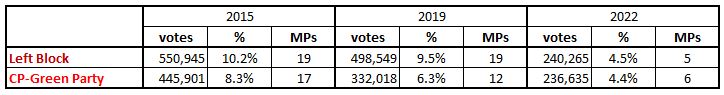

The table below shows how votes, percentages and parliamentary seats of the Left Bloc (which started as an alliance of radical anti-capitalist left organisations), the Portuguese Communist Party and the Greens (run on a joint ticket) developed in the last three elections.

They jointly had 1 million voters in 2015, but have now lost half of their support, occupying the 5th and 6th places respectively; from a total of 36 MPs, they now have only 11.

The reason for this slide lies with the political choices made by these two parties and their tactics towards the Socialist Party.

Portugal entered the turmoil of the financial crisis more or less at the same time as the other PIGS countries (Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain). In the 2015 elections, the right-wing Social Democratic Party of the then Prime Minister Coelho came first, but only elected 102 out of 230 deputies; it was therefore unable to form a majority government. The Socialist Party was second with 86 MPs and, along with 36 from the Left Bloc and the PCP, were able to get a majority in Parliament. After several years of memoranda, austerity and attacks to the lower strata of society, this was presented as an “opportunity” to get rid of the despised right-wing and to form a government which would potentially stop the austerity policies.

In this context, the two parties of the Left offered their vote of support/tolerance to the Socialist Party government and to A. Costa. This was initially supposed to be a “tactical” move by the Left Bloc and the PCP, in order to prevent the right from coming back to power. In practice, however, it ended up with the Left trapping itself, instead of exposing the Socialists and their limits, or instead of building a political alternative and reviving the movement.

The left parties have been constantly confronted with Costa’s blackmailing: that if they stopped voting for anything the government submitted, they would be held responsible for an eventual fall of the government and return of the right-wing. In this way, the Left Bloc and PCP voted for all budget proposals since 2015, except the last one, which caused the snap elections. They voted for the continuation of debt payments, for honoring the agreements with the Troika, supporting all bills for NATO armaments and even agreed to various cuts in public spending. In some specific cases, where the Left marked some red lines, Costa found willing allies on his right. Such was the case of the bills introducing changes in labour laws. In this way Costa managed to get two birds with one stone: remain in government with the votes of the left, and pass whatever law he wanted, sometimes with the votes of the right.

Thus, the parties of the Left entered a downward spiral. Year after year they gradually stopped being trusted and supported by the people, as they were not able to offer a convincing alternative, as they were seen tail ending the Socialists. In terms of the movements, they also became increasingly unreliable, as they came to face strikes and labour struggles organised against a government which they were helping to maintain in power. This has led to a de facto de-mobilization of their base because of the focus on parliamentary/institutional politics. Therefore, they ended up losing half their electoral power and disappointing sections of the working, popular and youth layers that used to support them.

The far right is consolidating

On the other side, the main beneficiary of the above disappointment was the far-right Chega party, which increased its support from 67,000 votes and 1 MP in 2019 to 385,000 votes and 12 MPs now.

The far-right has never managed to recover after the Portuguese revolution of 1974 that overthrew the military dictatorship. The financial crisis created the conditions for it to resurge. It is hard not to admit that the stance chosen by the Left bears a responsibility for the fact that the far-right managed to become a decisive factor in developments. The Left’s alignment with crisis management policies, coupled by an effective elimination of its radical content, has made the far-right look like the only opposition to the government.

Conclusions for the Left internationally

The fact that the Socialist Party succeeded in obtaining an absolute majority, has opened a debate on whether Portuguese society has made a rather “centrist” turn. Analysts connected to the “center-left” parties have tried to popularize such ideas.

However, the victory of A. Costa and the SP in these elections, is related mainly to a vote against the right-wing, with the hope to avoid a stepping up of austerity policies, rather than a conscious or even enthusiastic acceptance of a “less radical” project.

In other words, what has prevailed is the reasoning for a “lesser evil” vote. It is not the first time we have seen this historically. And it is the typical outcome when the forces of the Left fail to suggest a different way forward for the workers and the majority of society.

The political developments in Portugal can serve as a very useful lesson for the strategy of the Left around the world. The Left Bloc and the PCP could have built on their considerable appeal and could have turned their forces to the grassroots of society and the workplaces; this would prepare the movement to win victories and get results at the political level, through struggles. Instead of opting for this strategy, the Left Bloc and the PCP were caught in SP’s political game, which objectively led them to contribute in their own way to rescuing the system. Instead of unveiling the fact that the Socialists abandoned society’s aspirations midway, the Left voluntarily walked into a trap; in the end Costa just used them and then tossed them out like bad milk.

This is not the first time we witness such an unfortunate development. This is a repetition of what happened with the Rifondazione in Italy, but also with Syriza in Greece, to mention only two examples.

As long as the Left does not move in the direction of proposing radical changes and clashes with the establishment, it is doomed to repeat the same scenario again and again and betray the popular layers and its historical role. The Left internationally needs to draw the necessary conclusions, in order to break this vicious cycle.