Τhe first of the Moscow Trials started on 19 August 1936. On the occasion of this anniversary, we publish an article by written by Panagiotis Vogiatzis.

In August 1936, the world’s public opinion was stunned to find out that a vast conspiracy had been unveiled in the Soviet Union. Lenin’s old comrades and close associates, Zinoviev and Kamenev, as well as a number of well-known Bolshevik militants, were accused of having collaborated with the exiled L. Trotsky in organising to assassinate the member of Politbiro S. Kirov in ‘34. They supposedly planned to execute the remaining members of the government, sabotage the country’s production and transport and, in cooperation with the Gestapo, prepare for Hitler’s victory in the coming war! Most amazingly, the defendants themselves pleaded guilty to most of the crimes of which they were accused and were immediately taken to the firing squad.

The events caused a huge sensation. The defendants were well-known political figures who only two decades earlier had overthrown the Tsar and had played a decisive role in the establishment of the world’s first workers’ state. What had happened? Had they turned into sworn enemies of the workers’ movement?

Suffocating the revolution

The “Trial of the 16”, in 1936, marked the beginning of the final act in a drama which had started to unfold a decade earlier. The isolation of the revolution in a single country and the rise of the bureaucracy were gradually leading the Soviet Union into a situation of complete suffocation, which was no longer possible to hide. The Stalinist leadership had implemented internally a forced collectivisation of agricultural land, which devastated entire regions and led to the starvation of millions of people and eventually their death. Industrial production was growing rapidly, but at an enormous cost. The living conditions of the workers were even worse than at the early industrial revolution in the West. Huge projects, built hastily and without elaborate planning, were left unfinished. Explosions and disasters at factories and mines occurred too often. Things were no better at the foreign policy field. The disastrous theories of the “third period” and “socialfascism” led to the defeat of the revolution in a number of countries; in Germany these theories were practically responsible for handing over power to Hitler without a fight. It was a matter of life and death for the bureaucracy to find a scapegoat for all these disasters.

L. Trotsky and the Left Opposition around him had foreseen this development at an early stage. As early as 1926, at a meeting of the Politburo, Trotsky openly accused Stalin of “preparing to dig the grave of the revolution”. Three years later, and before the consequent wave of internal terror, Trotsky predicted that “the bureaucracy is bound to cut a river of blood that will separate it definitively from the real Party”. This was about to come true in the most painful way.

By the time of reaching the climax of 1936-38, Stalin proceeded in a relentless yet cautious way. Although he had managed to completely dominate the internal life of the party, the Bolshevik traditions were still strong. At the beginning of the 1930s, he had not yet succeeded in imposing his absolute personal domination over the Party: the latter constantly resisted whenever the question of physically exterminating the “enemies of the people” came up. Thus, in a series of public trials, starting with the “Shakhty Trial” in 1928, and passing on to the cases of the “Industrial Party” and the Mensheviks in 1930 and the “Ryutin Platform” in 1932, all the elements that would prevail in subsequent trials, namely the complete lack of real evidence and proof, the imaginary confessions of the accused, etc. were there. Yet, he had not succeeded, despite his efforts, in carrying out executions. The turning point in this process was Kirov’s assassination in December 1934.

Kirov

We know today that Kirov was not “a third-rate bureaucrat” as Trotsky qualified him in his writings of those times. On the contrary, he was the rising star of the leadership group, a member of the Politburo and in charge of Leningrad, the most important party organisation. As he had introduced some nuggets of liberalism into his region, some felt that he could be a counterweight to Stalin himself. Indeed, he was first in votes for the Central Committee at the 1934 congress and a small group of delegates considered nominating him for Secretary General. It is therefore obvious who would benefit from his death…

Although no hard evidence has been found, it is safe to conclude that, even if the secret services, namely Stalin himself, were not actively involved in Kirov’s assassination, they were certainly aware and tolerated it. His assassin had been arrested armed outside the party offices in Leningrad a few days before, but was immediately released. Kirov’s personal guard was killed two days later in a car accident in which no one else on board was hurt! In any case, Kirov’s death marked the beginning of the largest operation of state terrorism ever to take place in the entire world.

Hundreds of people were condemned in summary procedures and shot over the next two months. Zinoviev and Kamenev, as well as other former opposition members, who had been in exile for over two years, were retried (but the trials were still held behind closed doors) and the accused were forced to take over the “moral responsibility” for the murder. The sentences were still comparatively light – 5 to 10 years in prison. Terror was slowly and cautiously being organised. But soon the developments would snowball.

The climax

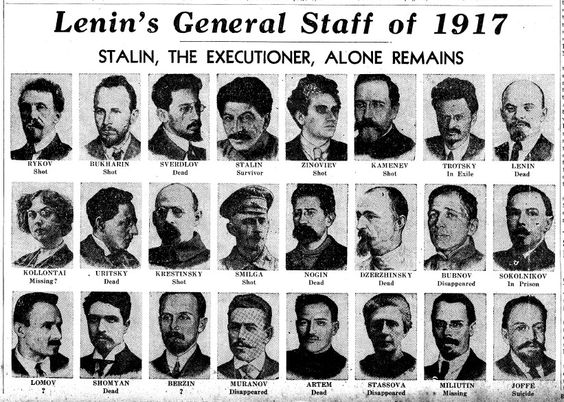

During the next three years, between1936 and 1938, three major open trials were held. The first took place in August 1936, the second in January 1937 and the third in March 1938. In between, the trial of the generals took place in May 1937. In these procedures, the entire old generation of Bolsheviks was exterminated and the Red Army was beheaded. Among their victims were all the former members of the Politburo, from 1917 onwards: Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, Rykov, Tomsky – who managed to commit suicide just before he was arrested, Pyatakov – who is referred to in Lenin’s “testament” as one of the most competent Bolsheviks of the new generation, I. N. Smirnov – nicknamed “the conscience of the Party” for his bravery and impeccable character, Rakovsky – who was the pioneer in building Communist Parties in Bulgaria, Romania and Ukraine, Krestinsky and Serebryakov – secretaries of the Central Committee in Lenin’s time, Mrachkovsky – a worker born in prison by revolutionary parents, Drobnish – who was almost killed by the Whites during the civil war but survived quite by accident, and dozens of others.

But this was only the tip of the iceberg. An unprecedented massacre was taking place at the same time across society, tearing the country apart. In the years 1937-1938 alone, according to official figures of the time, 1.3 million people were deported and executed. Even more were sentenced to somewhat lighter sentences. Terror reigned everywhere, paralysing any creative initiative and any appetite for work. Every second family had a member in exile, in prison or in the grave. Siberia was filled with forced labour camps, the “gulags”, where prisoners died like flies, most often working on construction projects that immediately fell into disuse. The few survivors describe in their memoirs, conditions unbelievable to even the most morbid imagination.

Many wondered what happened as the terror seems to “suddenly” stop around 1939. But the reason is extremely simple and based on mathematics, since every arrested person was required to turn in at least 3-4 more. So, by early 1939 5% of the population was caught in the net of this horrible absurdity. If this situation had continued for a few more months there would have been no one left to be arrested. As creepy and paradoxical as it sounds, the “liberalization” of 1939 was largely due to the limited number of potential victims…

Terror, of course, never stopped completely, either during the war or even immediately afterwards, when the country was experiencing the euphoria of victory. Only the targets became more specific (displacement of entire ethnic groups, the cases of the Doctors, the Jews, Leningrad and so many others). The gulags continued to exist for decades after Stalin’s death.

But why did they confess?

The biggest “mystery” surrounding the Moscow Trials from the very first moment were precisely the confessions of the accused. The Trials were based entirely on their confessions. In cases where thousands of conspirators were allegedly involved, not a single piece of tangible evidence, not a single incriminating document was presented. Whenever this was attempted, the bureaucracy was ridiculed. In one case, a meeting was supposed to have taken place at a hotel in Copenhagen, but this hotel had been demolished 15 years earlier; in another case, Pyatakov had supposedly travelled to Oslo by plane to meet Trotsky, but at that time no foreign plane had landed in Oslo for months. So how was it possible for experienced and hardened revolutionaries to slander themselves and their fellow prisoners with such outrageous accusations? There was too much smoke, how was it possible that there was no fire?

This is yet another of the dozens of myths with which Stalinist forgery has fed history. When we look closely at these “confessions”, the mystery does not seem so big anymore. First of all, we need to take into account that this was not a one-time process. On the contrary, it was a long descent, which for most of the accused lasted for a whole decade. From 1927, when Zinoviev’s group decided to break away from the Opposition, in order for them to be allowed to re-join the Party, an almost irreversible process began. At first the oppositionists were asked to proclaim in political terms that the Stalinist bureaucracy was right and they were wrong. Shortly afterwards they were asked to admit that “their positions objectively helped the class enemy”, even though they were politically disarmed. Soon after they had to acknowledge that they bore “moral responsibility” for the actions of others, alleged terrorists and saboteurs. Then they were asked to denounce Trotsky, who supposedly was pulling the strings from exile, and so on. If at any point the accused decided that they could go no further, the bureaucracy would attack them: “Do you refuse to confess? Does that mean that all your previous proclamations were false? You don’t really want to help our socialist homeland” etc. At the same time, a pile of confessions of collaborators, assistants or relatives fell on them. Under these conditions, and as of course because the accused were also physically tortured and had their relatives threatened, it is natural that many of them were unable to cope with the pressure.

On the contrary, the circle of oppositionists around Trotsky understood in good time that no capitulation to the Stalinist regime was possible, so they managed to cope with the pressure, paying an even heavier price, of course. While the accused in Moscow were confessing to imaginary crimes, the Trotskyist prisoners in the worst Siberian camps were going on strikes and on hunger strikes, demanding better living conditions and were often falling dead under machine-gun fire. When amnesty was granted, after Stalin’s death, thousands of prisoners returned to their homes, but there was not a single Trotskyist among them. They had all been exterminated to the last one…

Some examples

But the confessions themselves, if read carefully, are very revealing about their sincerity and, above all, about the limits that were impossible for the prisoners to cross. We site here some examples from the official transcripts: At the first trial, Prosecutor Vyshinsky asks Smirnov:

Vyshinsky: When did you leave the [terrorist] center?

Smirnov: I did not have to leave it, there was nothing that I might have left.

Vyshinsky: Did the center exist?

Smirnov: But what center …?

The Prosecutor asks other accused, all of whom admit the existence of this “centre” and turns back to Smirnov, who ironically states:

“Since you absolutely want a leader for this Centre, then I will play that role.”

At the beginning of the third Trial, Krestinsky made the following statement:

“I do not recognize that I am guilty. I am not a Trotskyite. I was never a member of the ‘right-winger and Trotskyite bloc’ [this was the charge against the accused at that trial], which I did not know to exist. Nor have I committed a single one of the crimes imputed to me, personally; and in particular I am not guilty of having maintained relations with the German Secret Service.”

It took an overnight interruption of the trial and all-night efforts by the GPU (secret police) to get him to return to court the next day completely shattered and declare the outrageous:

“Yesterday, a passing but sharp impulse of false shame, created by these surroundings and by the fact that I am on trial, and also by the harsh impression made by the list of charges and by my state of health, prevented me from telling the truth, from saying that I was guilty.”

The most telling evidence of the “validity” of the trials, however, is included in Radek’s testimony at the second trial. During one of Vyshinsky’s usual curses (rabid dogs, snakes, scum, etc.), the extremely smart and witty Radek comes back to his old self for the last time and attacks him:

“What proofs are there in support of this fact? In support of this fact there is the evidence of two people – the testimony of myself, who received the directives and the letters from Trotsky (which, unfortunately, I burned), and the testimony of Pyatakov, who spoke to Trotsky. All the testimony of the other accused rests on our testimony. If you are dealing with mere criminals and spies, on what can you base your conviction that what we have said is the truth, the firm truth?”

Vyshinsky preferred to change the subject immediately.

Finally, it is also a lie that “everyone confessed.” The truth is that only those of the accused who were completely broken were presented at the open trials (although they, as we have seen, tried to maintain some shreds of dignity). Everyone else was shot in secret, most of the time without even a trial, or with “trials” lasting a few minutes. The bureaucracy itself, being so meticulous, had to be seen to provide us with an irrefutable proof. The files of the accused of the first Trial, numbered and in alphabetical order, go at least as far as number 38. Only 16 defendants were present at court though, so at least 22 others were meant to be judged but never made it to court…

The revolution devours its own children?

No one can anymore believe that there was even a shred of truth in these Trials. Even the bureaucracy itself was forced to partially refute them in the following decades and rehabilitate most of their victims (except of course for the main accused, Trotsky, who remained an “enemy” to the end). The damage from these trials though was enormous. Apart from the monstrous extermination of millions of innocents, the Revolution itself was discredited to the utmost degree. Many people made a superficial judgement and were quick to blame it as a whole. What value can a revolution have if it ends in this way? And yet, as we have explained above, the shame must not be attributed to the revolution but to the bureaucratic caste that usurped it and had to completely annihilate it, to turn it into its opposite, before it could advance its plans to consolidate its domination. All that remained of the October revolution, 20 years later, was the change in the productive forces it had implemented. Beyond that, also remained a handful of usurpers, with Stalin at the head, and a few hollow sayings. The Bolshevik Party of 1939 certainly had nothing to do with the party of the revolution, and there’s numerical proof of this; only 0.3% had been members of the Party before 1917! The main pillars of Communism, equality and internationalism, had been completely obliterated by the politics of the bureaucracy. They only remembered these forbidden words on anniversaries and used them to justify their own existence. Indeed, Stalin dug the grave of the revolution and went down in history as the most stigmatised person in it.

Horror in numbers

If horror and paranoia can be described in numbers, the Stalinist period has countless of them for us:

By 1940, all the members of the 1917 Central Committee who were not old enough to die of a natural cause, had been executed or vanished into thin air.

70% of the 1934 Central Committee members (who were all loyal Stalinists) were also dead by 1940. The same goes for the Party’s youth Central Committee, the Komsomol.

During the purges of the Red Army, some 35-40 thousand officers were exterminated, including 80% of those at the rank of Colonel and above. There is no other case in history, in which a conspiracy involving 80% of the highest officers, was not only exposed and defeated, but where not even a single battle was fought. Was this thanks to the determination of the political leadership? How is this possible when 70% of this leadership was also accused of being involved in the conspiracy?

We can witness a similar situation in the diplomatic service: while only 30 countries had recognised the USSR, 48 ambassadors were executed in the purges. As a result, on the eve of the war there was no Soviet ambassador in Washington, Tokyo, Warsaw and other capitals.

From a certain point on, eliminating conspirators became a kind of “task”, with the obligation to deliver a certain quantity within a specific period of time! A typical telegram from Yezov, chief of the secret police, to the head of the Kyrgyz GPU reads in a nutshell: “You have been charged with the task of eliminating 10,000 enemies of the people. Report execution”!

The workforce of the Soviet Union in 1939 included: 600,000 mine workers, 900,000 railway workers and … 2.1 million guards, prison guards and secret police officers, not including the special troops of the NKVD (Ministry of the Interior). When the war broke out and Hitler’s troops had surrounded Moscow and Leningrad, 250,000 elite NKVD troops were blocked in the concentration camps guarding the prisoners…

In 1935, the death penalty for children of 12 years old (!) was included in the penal code. Stalin’s servants justified this in the West by claiming that “under Socialism children grow up faster”! It must indeed have been the case, since there have been found in the archives statements by children of that age confessing that “they had formed a gang operating espionage and sabotage and having links with the Gestapo”…

It should be mentioned finally that the Trials have been described by some bribed Western lawyers as “jewels of the legal science”. They must refer to the defence counsel’s closing speech at the Bukharin trial:

“Comrades judges, the facts in this trial are so clear, … that the defence finds no reason to disagree with Comrade Prosecutor. …As for the political and moral conclusions, the Prosecutor’s speech was so comprehensive that the Defence feels the need to wholeheartedly endorse it…”