Giannos Nikolaou

The result of the second round of the French parliamentary elections on July 7, which placed the far-right Rassemblement National (National Rally-RN) party in third position in terms of the number of MPs elected, has caused relief and jubilation among large sections of French society.

This outcome was unexpected, as no poll or analysis had predicted either the New Popular Front (NPF) taking the lead or Le Pen’s party being relegated to third place.

Le Pen’s defeat

The French electoral system, with its 577 single-member constituencies and two rounds, as well as the withdrawal of some candidates from either Macron’s Ensemble or the NPF coalition to avoid splitting the vote against the far-right, makes interpreting the results and drawing conclusions quite complex.

However, a key element of the situation is that the far right in France suffered a defeat, despite scenarios predicting an RN absolute majority in the French National Assembly.

For the Left, for the mass movements, and especially for minority communities, the immediate threat of an extreme-right victory has been averted. This does not mean, of course, that the threat will not return. Moreover, the political situation remains fluid, and the challenges for the Left are enormous.

The results: How and what did French society vote?

The next French Parliament will be almost tripartite. The distribution of party/coalition power will be as follows (with changes compared to the 2022 elections in brackets):

– New Popular Front: 180 (+49)

– Ensemble / Together (Macron): 159 (-86)

– National Rally (Le Pen): 142 (+53)

– Republicans (traditional right): 39 (-25)

– Other/independents Right: 27

– Other/independents Left: 12

– Other/independents Centre: 6

– Other: 12

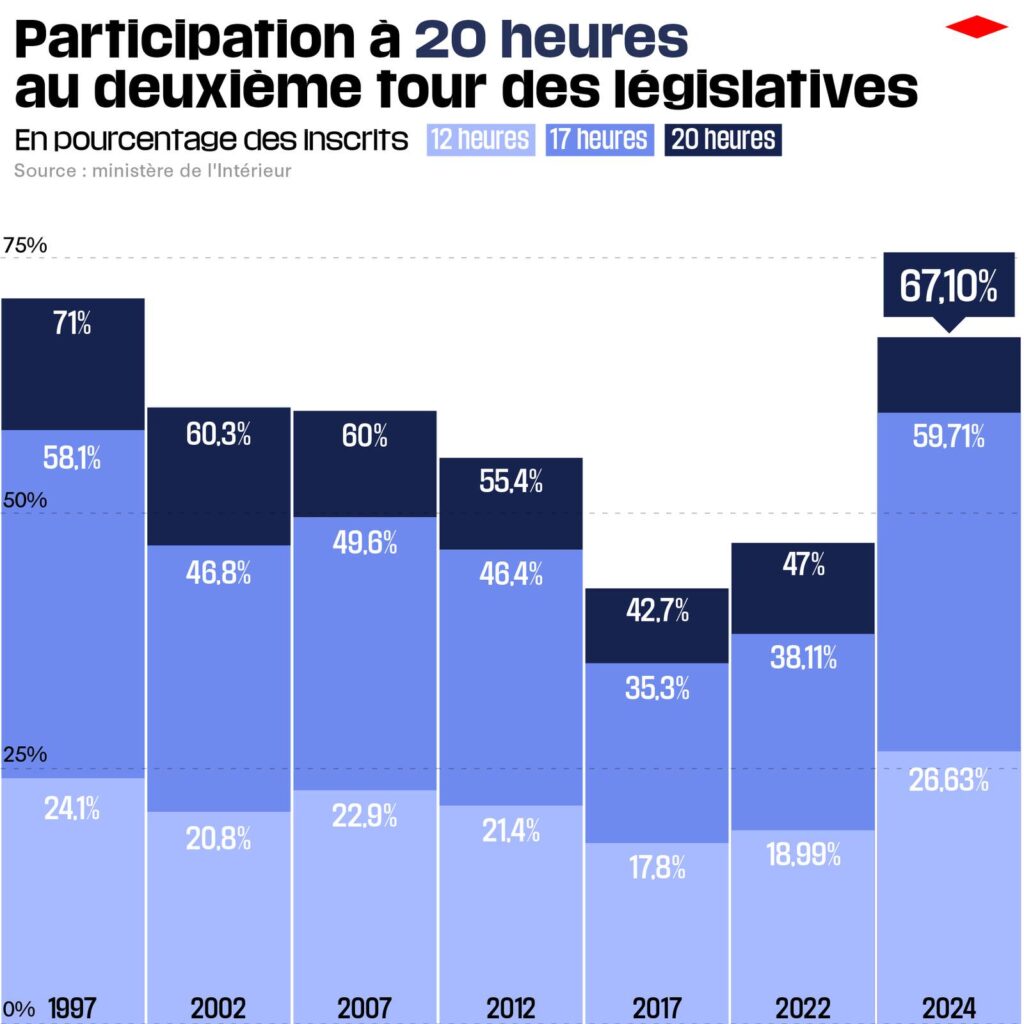

Turnout in the second round was over 67%, a record for French legislative elections, with the previous high being 27 years ago. In the last election in 2022, turnout was only 47%.

This increased turnout demonstrates the strong mobilization of French society against the prospect of a far-right victory.

This is one side of the coin, concerning the seats and the composition of the parliament. At the level of votes, however, the situation is more complicated.

In absolute terms, Le Pen’s party is in first place, with more than 10.6 million votes in the first round, compared to 9 million for the NPF and 6.8 million for Macron’s party.

This general picture was not reversed in the second round*, but the main reason Le Pen was not elected as the leading force in parliament is that in constituencies where there were three candidates in the second round, NPF and Ensemble (Macron) candidates withdrew to avoid the election of a far-right candidate.

This electoral tactic was not uniform everywhere. For example, Macron’s candidates did not withdraw when the NPF candidates were members of Mélenchon’s France Insoumise, showing how concerned the ruling class is about the leading role of the “far-left” wing of the New Popular Front.

However, the qualitative results of the first round of voting, as recorded in an Ipsos survey, reveal significant issues regarding the dynamics of the far right in French society.

For example, civil servants and the self-employed voted 32-35% for the NPF, while private employees and the unemployed voted 40% for Le Pen. The picture is even clearer (and more negative) in other categories: among those with lower levels of education, lower incomes, and generally “less satisfaction” with their lives, Le Pen came out on top.

On the other hand, young people voted overwhelmingly for the NPF (48% in the 18-24 age group, 38% in the 25-34 age group), while Le Pen’s party scored between 35 and 40% in the 35-69 age group. There is also a clear predominance of the NPF in large urban centers (cities with more than 200,000 inhabitants) compared to the provinces, which by majority supported Le Pen.

The games of the ruling class

If one looks at the picture superficially and only hears the “cries” of the far right that “Macron and the Left stole the elections from us,” one might think the ruling class was so afraid of Le Pen that it allied itself with the (left-wing) devil against her. But is that so?

To begin with, Macron’s center-right party is only one pole of expression of the interests of the ruling class. The other, is the Republicans, the traditional Gaullist right, whose president proposed an alliance with Le Pen against the NPF. Their position in the second round, where there was an NPF candidate against Le Pen, was to lean towards the far right.

Moreover, Macron’s attitude towards NPF candidates showed the ruling class’s worries over a strong left outcome: he was open to withdrawing his own party’s candidates if the other candidates in the second round against Le Pen were members of the Socialist Party, the Greens, or the CP, but not if they were members of Mélenchon’s France Insoumise. Additionally, Mélenchon was depicted by the mainstream media as “extreme” and denounced as “authoritarian”, in an attempt to undermine the more radical elements of the NPF.

Macron took the risk of calling early parliamentary elections in the immediate aftermath of the European election debacle, hoping to halt Le Pen’s rise. So far, it seems to have worked. However, the divided parliament portends a long period of political and economic instability, while the Left’s advantage introduces new issues to the table.

Political deadlock

At the moment, there is no viable scenario for a majority government, nor is there any party “close” to a majority seeking some “tolerance” votes. Additionally, there is no foreseeable scenario for a coalition government between two of the three main parties, although some statements by Macron’s officials and NPF “moderates” (such as the Socialist Party leader, Glicksman) speak of “responsibility and a broader consensus.”

This reflects the political deadlock that the capitalist system faces in principle. The political instability has already spilled over into the country’s economy, which is also affecting the EU – France’s borrowing rates have risen significantly, and the euro has fallen against the dollar. These are the reactions of the so called “markets”, i.e., the ruling class, which aim to impose –by economic strangulation if necessary– their own agenda on the political developments.

The “New Popular Front”

The New Popular Front in France is an alliance full of contradictions, as it brings together militant radical sections of the Left, mainly around France Insoumise, and at the same time, Socialist Party cadres, such as former president François Hollande, who bear huge responsibility for the problems experienced by the majority of French workers due to the SP’s austerity policies in past years.

As reported by Libération, there were different tactics within the NPF during the election period. On one hand, the members of France Insoumise were genuinely fighting for the best possible result, focusing on convincing those who abstained to vote Left. On the other hand, the more moderate wing of the NPF was looking for the “right electoral tactics” (deciding which candidates to withdraw and in which constituencies to ally with Macron) to prevent a possible Le Pen majority.

In the end, the big winner within the NPF from this election, as regards seats, is the Socialist Party, which managed to elect 59 of the 180 MPs in the alliance, doubling its strength from 30 in 2022. On the other hand, France Insoumise, which until recently had the upper hand in the alliance, elected four MPs fewer than in 2022.

The previous similar attempt in 2022, an alliance of more or less the same forces called NUPES, actually collapsed shortly after the elections. Now, the first position carries greater risks for such a contradictory alliance, especially if it is pushed even harder by Macron’s party in the name of avoiding ungovernability, of the so-called cordon sanitaire [the idea of a “democratic bloc” against the far right] and for stability.

The contradictory nature of the NPF is a significant problem that will sooner or later come to the surface. The NPF program contains a number of demands for important pro-working-class reforms (wage increases, lowering the retirement age, etc.), but it does not describe how they will be implemented given the country’s economic situation. It includes forces fighting for broader, though vague, system change (such as France Insoumise) and forces identified with a “left management” of French capitalism, the policies of which are precisely those that led to the rise of the far right.

The next day for the Left

French workers, minorities, and the majority of society have every reason to be relieved that Le Pen’s far-right National Rally has been relegated to third place. The youth, who voted overwhelmingly for the NPF and took to the streets against the far right, have every reason to be satisfied with its lead. However, this alone is not enough to effectively contain the far right or implement the pro-people measures of the NPF program.

The fact that the far right has “taken over” and managed to win over some of the most battered and working-class sections of French society is a problem that cannot be solved by electoral tactics alone or mainly.

What is needed is a turn to the grassroots of society, building links with the working class and poor neighborhoods where French society is boiling, and exposing the true role of the far right. All this can only be done through a radical and genuinely subversive political program that clashes with the interests of the system in order to serve the interests of the majority of society.

To achieve this, the Left (which essentially means France Insoumise and the organizations of the anti-capitalist space) must call things by their true name and not “move towards the center.”

This road is certainly very demanding; it requires building new forces of the Left in an anti-capitalist direction. It takes time and effort, but it is the only one that can put a real brake on the far right, send it to the dustbin of history, and at the same time overturn the policies of systemic parties like Macron’s.

________________________

Historically, the policy of Popular Fronts has often led the movement and the Left to significant defeats. Popular Fronts referred to partnerships between working-class parties and the Left with sections of the (supposedly) “progressive” ruling class. The term emerged in the 1930s, when the Stalinist Communist International sharply shifted its policy away from the previous strategy of United Fronts.

United Fronts, developed by the Bolsheviks and the Communist International before it came under Stalin’s control, involved cooperation or joint action by workers’ and left parties (without parties representing capitalists) on specific issues, while maintaining the full independence of all participants.

Wherever Popular Fronts were implemented, we saw the subordination of workers’ and left parties to the aspirations and policies of ruling class parties, leading to the destruction of prospects for social change. Examples include Spain in 1936, Chile in 1973, and Greece in the 1940s, among others.

* The absolute numbers from the second round do not provide a straightforward basis for safe conclusions. This is because, firstly, 76 out of the 577 MPs were elected in the first round, meaning those constituencies did not vote in the second round. Secondly, the strategic withdrawals of NPF and Ensemble candidates in constituencies with three candidates in the second round—aimed at preventing a far-right candidate from winning—complicates the clear interpretation of their vote totals. In contrast, there were no withdrawals of far-right candidates, making their vote totals in the second round appear larger relative to the Left’s results than they actually are.