Nigel Smith

April 8th marks the tenth anniversary of the death of ex-UK Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher. Thatcher is one of the most significant British political figures of the last one hundred years. This is not only because she was the UKs first female Prime Minister, but also because of her impact on the political and economic character of the United Kingdom. It is also the case that her neo-liberal approach along with that of US President, Ronald Regan had a profound influence on global capitalist economics.

Sworn neoliberal

Thatcher was elected Prime Minister for the first time on May 4th, 1979, winning two further terms in office in 1983 and 1987 before finally being forced to resign by her own Conservative Party after eleven years as Prime Minister in 1990.

Thatcher was heavily influenced by her right-wing political mentor, Keith Joseph , who was himself influenced by the neo-liberal ideas of Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek. Thatcher and Joseph encouraged the media to use the term Thatcherism to describe her ideas about society and the economy. This was in order to promote the notion that Thatcher was somehow a visionary. Much was also made of Thatcher’s background in chemistry – she got a second-class degree in chemistry as well as her modest beginnings as the daughter of a greengrocer, although her father did become Mayor of Grantham.

Thatcher portrayed herself and her supporters as politically robust and denigrated opposing Conservatives within her own party as “wets” (politically weak). As Prime Minister she effectively purged her cabinet of so-called wets, in order to face little opposition to her neo-liberal agenda, which some in her party saw as extreme.

Thatcher’s approach to the economy was to ferociously support the interests the banking and finance sector over those of industry and working people. She set forth on a mission of mass privatisation of Britain’s nationalised industries and also commenced a process of selling off, at knock-down prices, the council houses that had been built to house working people, both between the two World Wars and after the Second World War. In doing this her government received a cash injection of funds, which in no way represented the real value of the industries and capital goods sold. She also supported the closure of significant sections of British manufacturing, so that the steel, ship-building and car manufacturing industries were either obliterated or massively reduced. During her reign as Prime Minister, Britain began to move from a manufacturing economy to a services-based economy at a rapid rate.

Thatcher over-saw the shutting down of manufacturing right across the economy, arguing that Britain could profit from success in services. This led to unemployment rising from less than one and a half million to over three million in under two years. Thatcher put monetary policy ahead of jobs. She increased interest rates in order to slow the growth of the money supply and therefore lower inflation and this put pressure on businesses and increased unemployment.

During Thatcher’s first term in office, many in her party saw her as a lame-duck prime minister and she was counselled by some senior ministers to quit. This led to her famous remark at the 1980 Tory Party Congress of “The lady’s not for turning.”

Thatcher remained unpopular with the British people, but in April 1982 the Argentinian Junta invaded the Falkland Islands. Immediately prior to the invasion, Thatcher had talked of significant cuts in naval spending but following the invasion she ordered a task force to sail to regain the islands from the Argentinian forces. The British task-force was composed of highly skilled, fully professional troops, who were pitted against a weak, poorly equipped and poorly trained Argentinian force. The victory was quick and decisive. Thatcher cynically used this war to bolster her popularity at home. She fostered the image of being at one with the armed forces and posed for the media as though in command of a battle tank.

Crushing unions

Thatcher understood that to achieve her wider political ambitions she would have to break the unions. Thatcher had a deep contempt for trades unionism and had seen Edward Heath’s Conservative government fall in 1974, largely because of the strength of the trade union movement. Following a land-slide victory in the 1983 election, Thatcher felt emboldened to take on the working class. She provoked a strike by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) at a time to suit the government, having built up massive supplies of coal to Britain’s coal-fired power stations. The strike lasted for one year, from the 6th March 1984 until 3rd March 1985. Throughout the strike, the miners were largely isolated and although supported by working class people, trade union movement’s support was too little and lacked coordination and determination. Thatcher used the full force of the state machine against the strikers and the police played a significant role in this. Police officers were transported from London to the North of England to confront the miners, often violently and two miners were murdered as a result of police action. Many miners were also wounded and the events at Orgreave colliery, where police attacked the workers with brutal force, and which are still the subject of state secrecy.

The defeat of the miners strike was a significant defeat for the working class in Britain and this was followed by a long period of retreat by unions and the subsequent loss of trade union rights. The Thatcher government took a strategic approach to the strike by provoking it in the way they did and trade unionists can learn a lesson from this example; don’t allow your enemy the benefit of choosing the form and timing of struggle.

Privatisations

The Thatcher government continued apace with its neo-liberal agenda, privatising telecommunications, which according to Jacob Ward (Computer Models and Thatcherite Futures 2020) was, “a landmark moment for neo-liberalism.” This approach became a model for other countries to follow in selling their state utilities.

Indeed, it could be argued that Thatcher developed an exaggerated mania in support of market forces. The Westland incident was an example of Thatcher promoting US, Sikorsky helicopters over the British Westland helicopters, to the detriment of national interests.

Thatcher was fiercely anti-socialist and anti-communist and denigrated these ideologies probably without understanding them. When asked to characterise socialism she merely answered by saying that it is a system offering government support to inefficient industry.

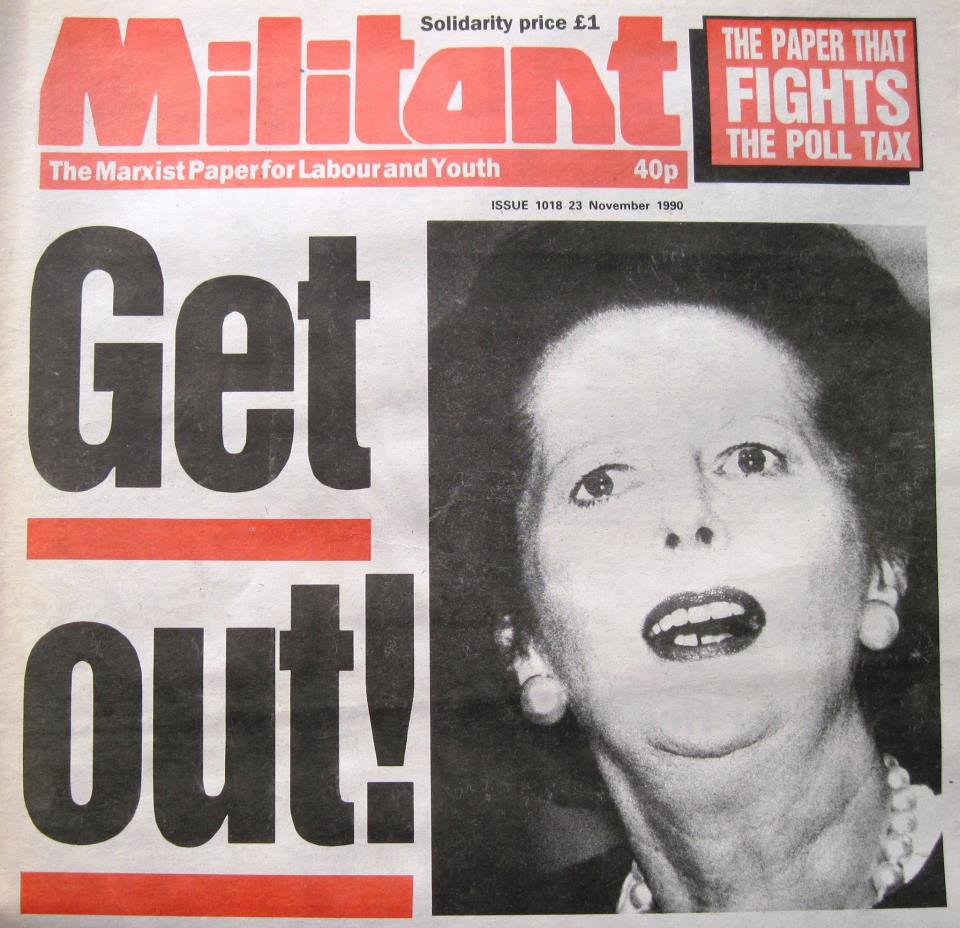

Towards the end of Thatcher’s reign as Prime Minister she came under attack from within her own party. Her anti-European stance in refusing to allow closer ties with Europe proved unpopular with many Tory ministers and her leadership began to be questioned once more. However it was her extremist poll tax policy that eventually led to her downfall. The poll tax was a universal local tax applying equally across all levels of income. This was seen by more and more of the British people as what it was, incredibly unfair and fundamentalist. Thatcher’s political judgement began to be called into question and opposition to the poll tax grew. This opposition was coordinated by activists groups, with the Militant tendency taking a leading role. It was successfully resisted through a process of citizens refusing to pay the tax. Many were taken to court but the courts were clogged up because of the numbers involved and an approach of slowing down the judicial process as much as possible. As many as eighteen million households refused to pay. There were riots in several cities and a big increase in support for the Labour Party. All of these factors combined to indicate to the Conservative Party but also to the British people that, Thatcher’s time was up. Thatcher resigned from office on 28th November 1990.

Thatcher shunned parliament following her resignation and stood down as an MP in 1992.

Changing Labour

Many political commentators would agree that on top of her service to neo-liberal ideas, her greatest achievement was the transformation of the Labour Party into the neo-liberal New Labour Party. The current Labour Party, not with-standing the temporary phenomenon of Corbynism is at least as right of centre as New Labour was. Tony Blair was a champion of the free market, including inside the NHS and although Labour governments tend to spend more on public services than Conservative ones, the real policy differences are marginal. Neil Kinnock as leader of Labour for much of the time in opposition to Thatcher was far more aggressive in challenging socialists in his own party than in challenging Thatcher. He prepared the ground for Tony Blair who became the darling of the City and the ruling class.

Today, Keir Starmer shows the Labour Party as safe for capitalism and neo-liberal capitalism at that. He has led a witch-hunt against left-wing voices in his party, leading to the suspension of Corbyn on trumped up charges of antisemitism. Recently, Starmer was unable to take a position in support of teachers and other workers in dispute with a government that refuses to negotiate meaningfully with them. This is because if in government, Starmer would attempt to take a similar position to the one adopted by the Conservatives.

Time to get rid of Thatcherism

So, Thatcher’s legacy lives on through the behaviours of the political class both at home and abroad. Her achievements are lauded by the capitalist class and the British media but she is hated by many in the working class. She was an enemy of that class and her influence in leading to the erosion of workers rights and working conditions, still persists.

The current wave of strikes that are taking place is an opportunity for the working-class to show its strength and begin to fight back against the neo-liberal ideas that Thatcher spawned as well as the ideas which are closely linked to Thatcherism promulgated by both the Conservative and Labour parties.

Thatcher is dead – long live working-class solidarity.