Fang Chang

Today marks the 33rd anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre, the day the Chinese Communist Party’s dictatorial regime crushed the revolutionary movement of 1989. It is important to note that the Tiananmen Movement was not an isolated political event, but part of a wave of struggles and mobilisations. While these movements were initiated primarily by students, the Chinese working class also played a crucial role in them.

Background

In the 1980s, China’s social development became increasingly rugged and unstable as a result of the process of capitalist restoration, initiated by Deng Xiaoping. The CCP regime began to encourage individuals to set up businesses and massively privatised public companies, which led to the growing corruption of local bureaucrats. In addition, Deng broke the promise of job security for workers in State-Owned Enterprises [1] and deregulated commodity prices, causing prices to rise faster than wages. That led to a 30% inflation rate in the first half of 1988. To cope with the price hikes, people had to withdraw cash from banks in order to buy goods whose prices were soaring, at a time when the general spending power of the working class dropped by 100% or more compared to 1983. These developments impacted on the standard of living of the working class, which fell sharply.

In an attempt to regain control of the economy, the Chinese central government urgently tried to decrease money supply and control credit, with the aim to stabilise the economy through austerity. The direct result of the government’s credit control was that many loans defaulted. A lot of Township and Village Enterprises in rural regions failed, resulting in the skyrocketing of the unemployment rate. Millions of workers lost their jobs. This is one of the reasons why, in the late 1970s, after the stringent household registration system was loosened, a huge wave of the rural population began to migrate to the cities in an attempt to find employment opportunities.

The movement arises

The more drastic impacts appeared in early 1989. As a result of declining living standards, social unrest and corruption, the anger of the masses built up and dissatisfaction with Deng’s regime was gradually rising. The death of former General Secretary Hu Yaobang on April 15, 1989, served as a spark. Students were able to use the mourning of Hu as an opportunity to launch a struggle against political corruption and for freedom of association and the press. Workers also joined the struggle.

An editorial published by the regime in the People’s Daily on April 26, titled “We Must Take a Clear-cut Stand against Disturbances,” used terms such as “unrest” and “conspiracy” to smear the democratic movement and pave the way for a ban on demonstrations and marches. This undoubtedly infuriated students and led more young people to take to the streets. At the same time, workers and citizens donated materials to support the students’ struggle. On May 4, on the 70th anniversary of the May Fourth Movement [2], 300,000 people gathered in Tiananmen Square to express their discontent with the Deng Xiaoping regime. Between May 15, when Gorbachev visited China, and May 17, more than half a million to a million people, including workers, teachers and students, gathered in Tiananmen Square in what was arguably the largest mass movement since the success of the Chinese Revolution in 1949.

These movements were a direct threat to Deng Xiaoping’s regime, prompting him to try to stop their spread by declaring martial law on May 20. However, public anger over inflation, commodity prices, corruption, and bureaucrats entering private businesses had reached its peak, leading to massive resistance to the martial law. Between May 21 and 23 alone, there were two separate anti-martial law marches and protests involving over a million people. These revolutionary movements spread to almost every corner of China, and industrial workers joined in by going on strike.

Mistakes in strategy

Despite their important contribution to the revolutionary movement, the leadership of the student’s movement also made crucial political mistakes. One of them was the lack of a clear goal and a political program for the movement, which made the organisation of various groups rather loose. However, the biggest mistake was the students’ refusal to incorporate workers in the revolutionary movement. Many elitist students believed that workers’ participation would undermine the democratic movement. They even tried to prevent workers from entering Tiananmen Square before the army surrounded Beijing. Evidence that came to light in the aftermath of the events, showed that the students underestimated the motivation of the workers.

After May 4th, the student movement started to wane. Many students returned to campuses. At the same time, however, the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation, was still actively recruiting and organizing workers, even planning for a general strike in support of students and distributing flyers against CPP’s dictatorial rule. On May 20, many workers and citizens spontaneously formed barricades and human barriers to stop the army from entering Beijing. They even formed the Workers’ Patrol to maintain order in the city. At the end of May, a hundred thousand workers at the Beijing Steel Mill were planning to go on strike.

Tragically, the students did not realize the importance of industrial action. Some students even considered the moderate politician Zhao Ziyang as the leader that could lead them to victory. In reality, both the “moderate” and the “hardliner” factions of the regime were responsible for privatization and corruption – they were both in favor of capitalist restoration. As a result, the movement missed an important chance to escalate and corner the regime. The Deng administration was given two weeks of breathing space, and in the end managed to mobilise an army of 200,000 to systematically and brutally crush the movement.

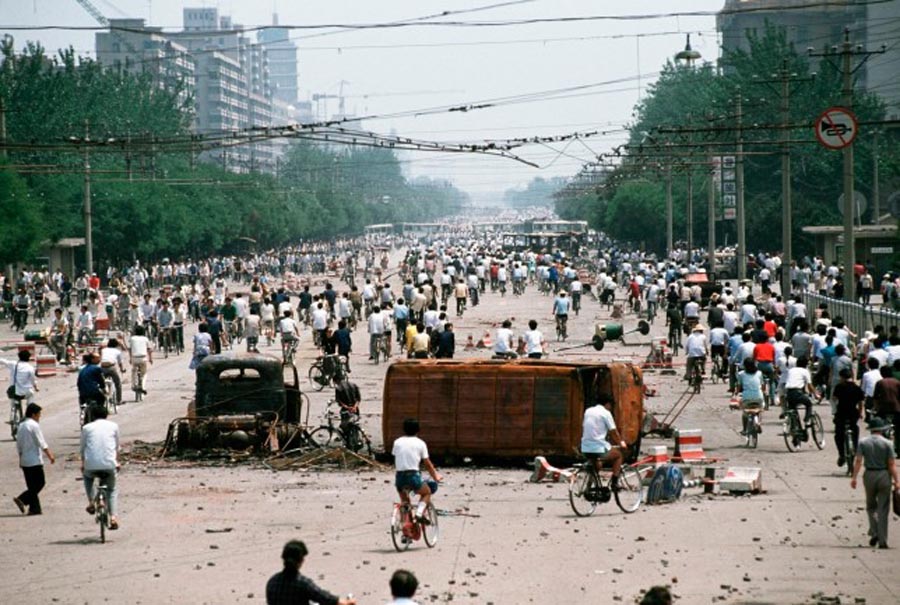

Bloody crackdown

In the late hours of June 3rd, a huge military force entered Beijing. Soldiers armed with tanks and machine guns opened fire on unarmed workers and citizens. Deng crushed the revolution of 1989 in a bloody massacre. Contrary to the common belief, there were not so many deaths on Tiananmen Square itself. Most of the killings happened in other areas of Beijing. The number of dead and injured students was also far fewer than the numbers of workers and other citizens. There are different estimates about the number of dead and injured during the crackdown, but it seems that more than 500 were killed and a few thousand suffered injuries. According to first-hand accounts of students, soldiers put dead bodies in bags and cremated them in the countryside. They even used bulldozers to move the dead bodies. To further weaken the working class after the massacre, the Deng administration went on to arrest forty thousand workers, and sentenced hundreds of them to death.

The period after

The Tiananmen massacre and the purge that followed crushed the political power of the Chinese working class, enabling the Chinese government to proceed with the restoration of capitalism and become the “world’s factory” by exploiting Chinese labor in sweatshop conditions. In an inter-imperialist competition, this eventually led to the challenging of the dominance of US imperialism on the world arena. However, it left Chinese society in a deep social crisis. The 30 years of oppressive rule since then did not bring a lasting social peace, but just managed to sweep social tensions under the carpet. These contradictions will explode at some point. The working class and the youth of China, Hong Kong and Taiwan must prepare themselves for that day, and be ready to act in order to bring down the CCP regime and establish a truly democratic socialist society.

[1] In 1984, these workers accounted for 40% of the total number of workers in China

[2] A 1919 students movement against the signing of the Versailles treaty